Chapter Four – Religious Fanaticism

By the time I completed the second grade at just six years old, my father had already decided our lives would once again be uprooted — this time to follow the ministry of a preacher named Steven Shelly. That decision moved us from our simple hut in the Philippines all the way to Alabama.

We first lived in Columbus, Georgia, inside Steven Shelly’s bus until my parents managed to scrape together enough to buy a mobile home. From there, we relocated to his 60-acre compound in Smith Station, Alabama. We were among the very first families to move onto the property as his so-called “tabernacle” was being built. Two small prayer chapels were erected first, each containing bins of ashes and a sackcloth cloak for those who wished to kneel in the ashes and pour them over their heads. Later, a larger tabernacle was built: a tin-roofed structure with a sawdust floor laid over the red clay.

Finances were always tight. We often relied on expired canned food purchased from flea markets. To make ends meet, my mother and I sold crafts out of the trunk of our car in store parking lots. For all of our sacrifice, the promises of “faith and blessing” never seemed to materialize. After six months, the truth came out. Shelly’s own father exposed him as a fraud, revealing that his life story had been fabricated and that he was exploiting the faithful for financial gain. A friend told me later that Shelly had privately told her parents we didn’t even possess the Holy Ghost and were not welcome on his “Ezekiel’s Wheel” property. We left shortly after, disillusioned but not yet free.

From Alabama, we moved again — this time to Mesa, Arizona, where my father aligned with Ray Carpenter’s church. This group clung to the “return ministry” doctrine of William Branham, believing Branham would literally be resurrected to fulfill prophecies left undone. It was during these years that I had my first encounter with computers. Something about technology fascinated me. I began to teach myself graphic and web design, even though the environment I was raised in discouraged women from pursuing education or careers. According to the message, my future was supposed to be confined to cooking, cleaning, and child-rearing while my husband provided. Years later, even as an adult, I was publicly criticized by a preacher for working in an office — proof that the idea of women pursuing independence was still treated as rebellion.

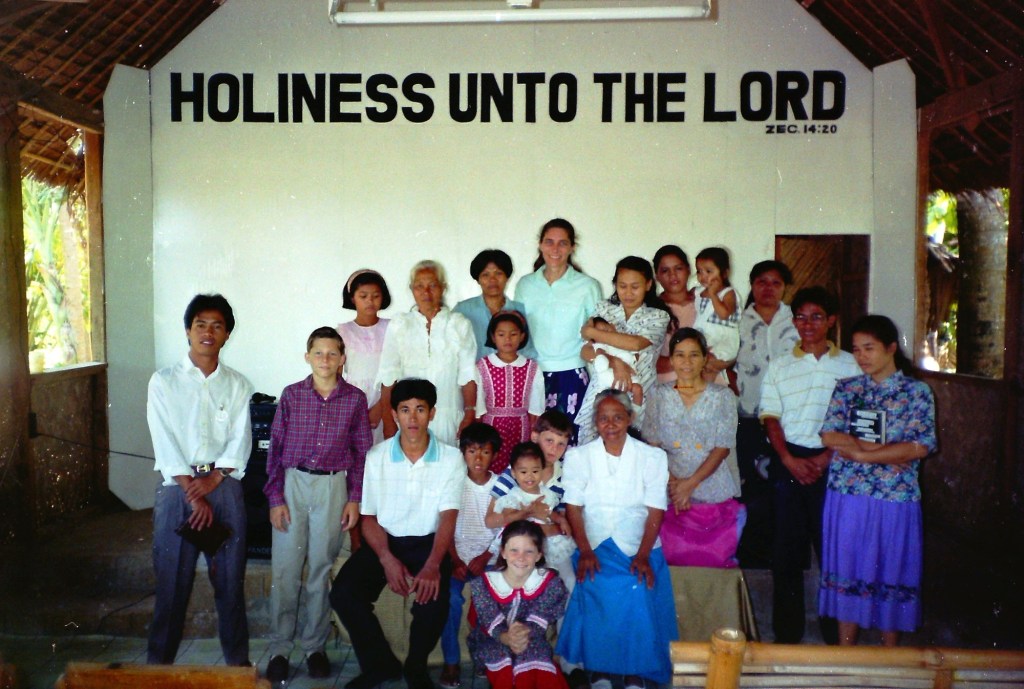

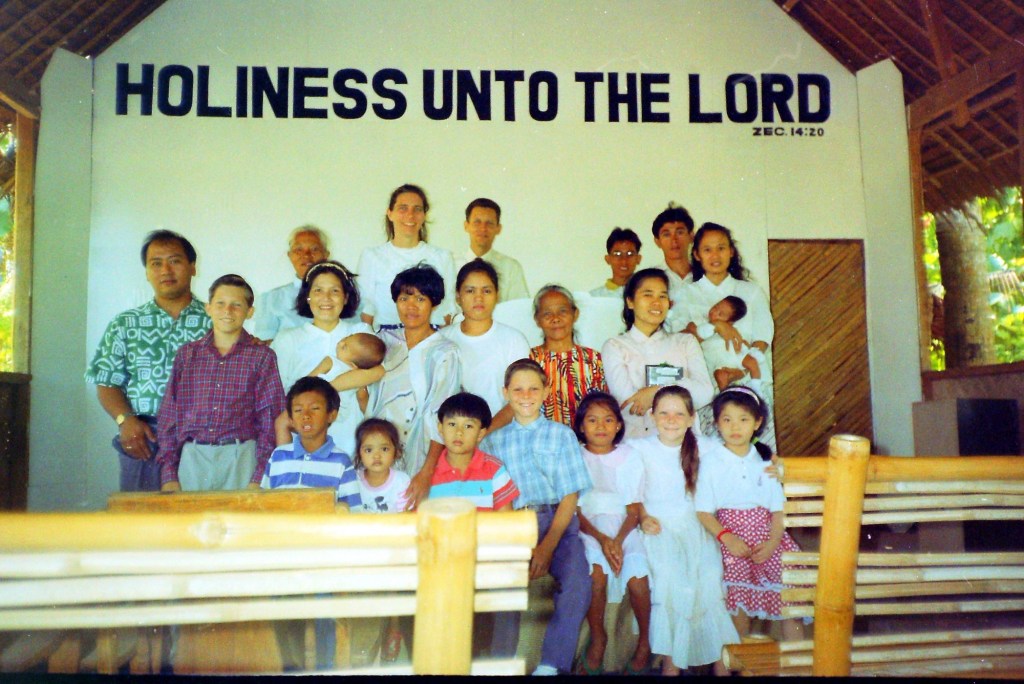

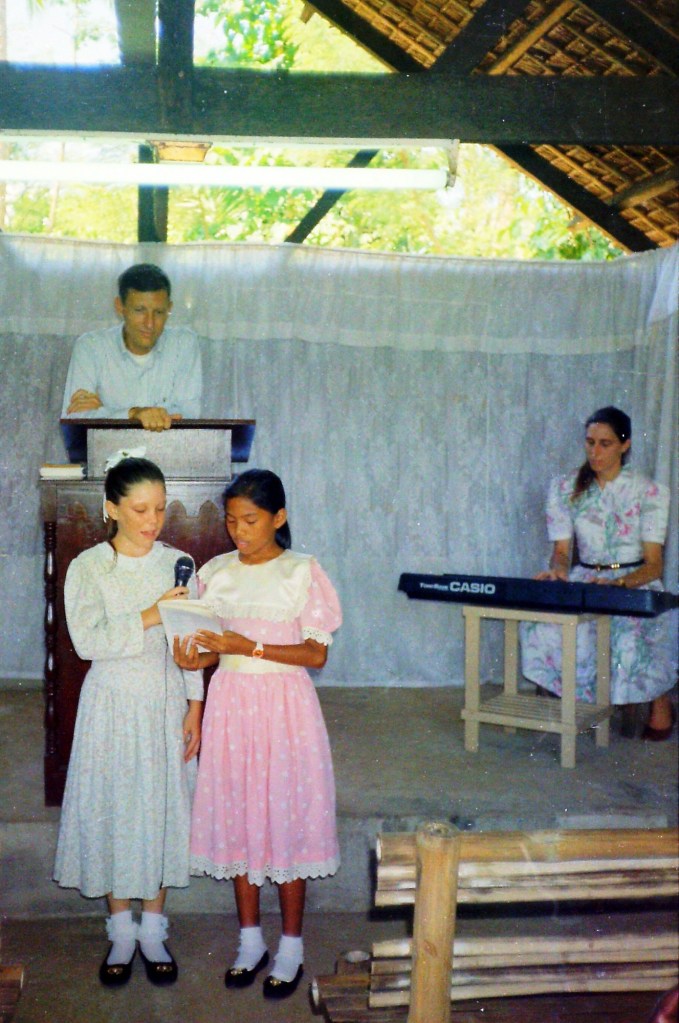

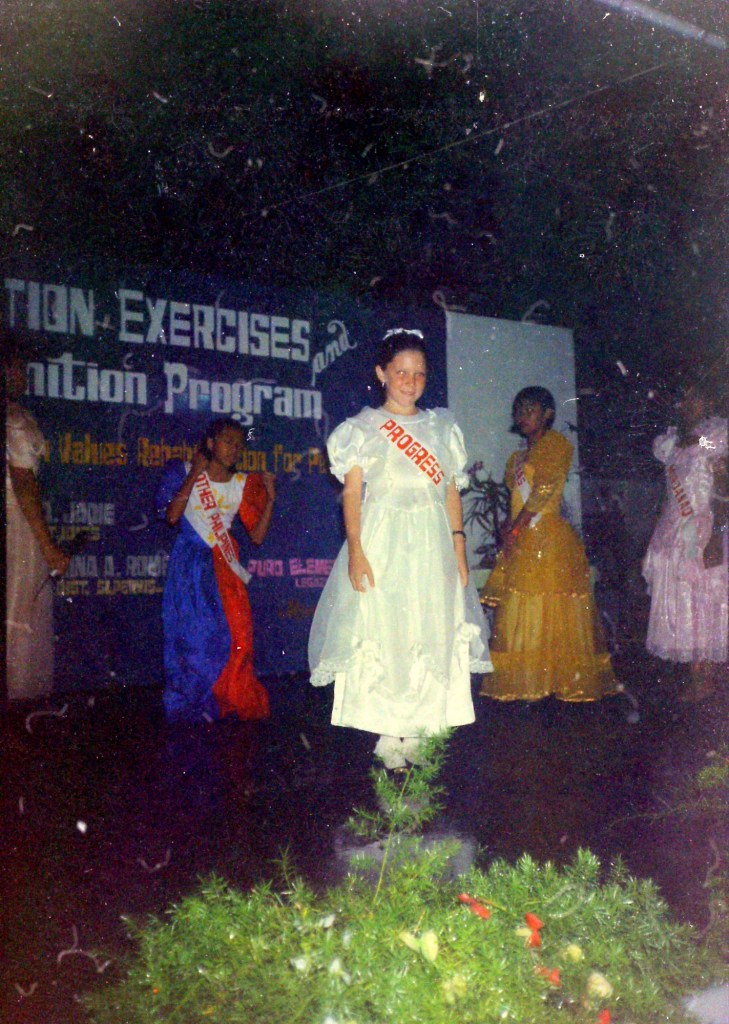

When we returned to the Philippines, things only became darker. My father became entangled with a man named Willy Hosanna, who was secretly abusing girls within his cult. Shockingly, my father wanted to bring Willy and his followers back to the United States for missionary work. My mother was devastated. She longed to leave the Philippines, but my father prioritized mission work over his own family. When the truth about Willy’s abuses surfaced, he left the church — but the damage was done. His devotion to “the message” always outweighed his devotion to us.

Life at home reflected that imbalance. My father was selfish to the point of absurdity. He would buy butter just for himself, telling us not to touch it, while giving us cheap margarine. He could act so holy and religious, yet his private reality revealed a man who cared more about control than about his family. He spoke in tongues and “prophesied” whenever my mother questioned him, declaring, “Don’t question God,” or, “This is God speaking,” or even, “God will strike you dead.” He used fear like a weapon, and it worked. My mother was forced to go to work to support us while he slept and prayed, claiming God would provide.

We lived on the equivalent of about $6 a week. My father had loaned huge sums of money to others in the church and we were left begging a woman named Tabuena for repayment of her debts. I will never forget watching him grab a man named Abraham by the shirt, shaking him violently and even punching him in the chest to demand repayment. I was six years old, and the rage etched on his face in that moment is burned in my memory. The man I ended up marrying reminded me of that version of my father.

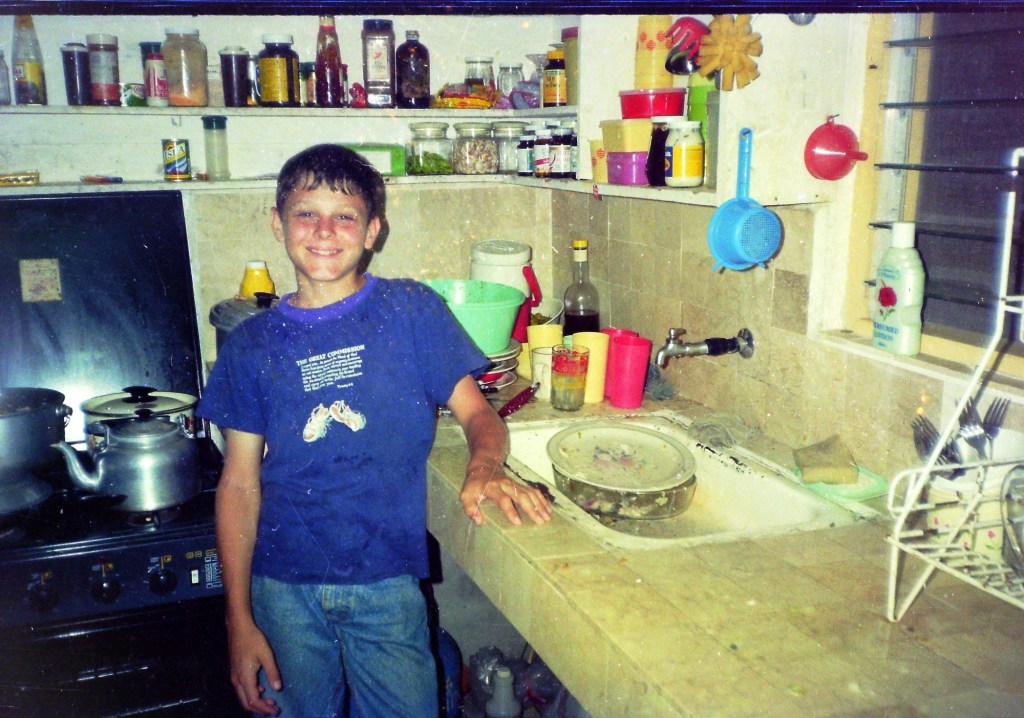

Our home life was chaotic, unstable, and often cruel. When I was five, a girl came over to play and wrote on my wall in chalk. My brother Josh told my mother it was me, and despite my protests, she and the girl’s mother spanked us both with belts — over and over, at least twenty times each. Finally, the girl confessed, but only after I had been forced to apologize in front of everyone, including my childhood crush, humiliated into admitting something I hadn’t done. That would be the first of many times Josh’s lies led to me being punished unfairly.

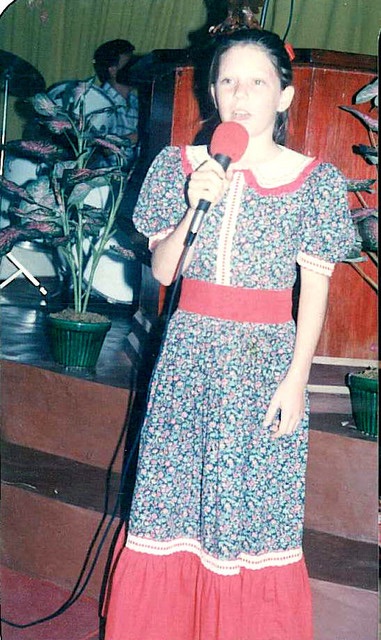

At seven, survival became a family project. My mother and I made crafts and keychains to sell. Josh would take them into town to peddle, or we would ride the bus and hand out envelopes marked Spirit and Life Ministries, asking for money in the name of missionary work. We would dump the coins and bills on the table at night, counting what we had begged from strangers. My father took those offerings and used them to start selling sewing machines and televisions wholesale.

My childhood was filled with contradictions. I was told Cinderella was of the devil, and once had hands laid on me in prayer for reading Sleeping Beauty. Yet when my father wanted to watch Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman, suddenly television wasn’t sinful anymore. The rules bent to his desires, and we were expected to fall in line. It planted in me a pattern of extremes, swinging between rigidity and permissiveness, depending on who held the authority.

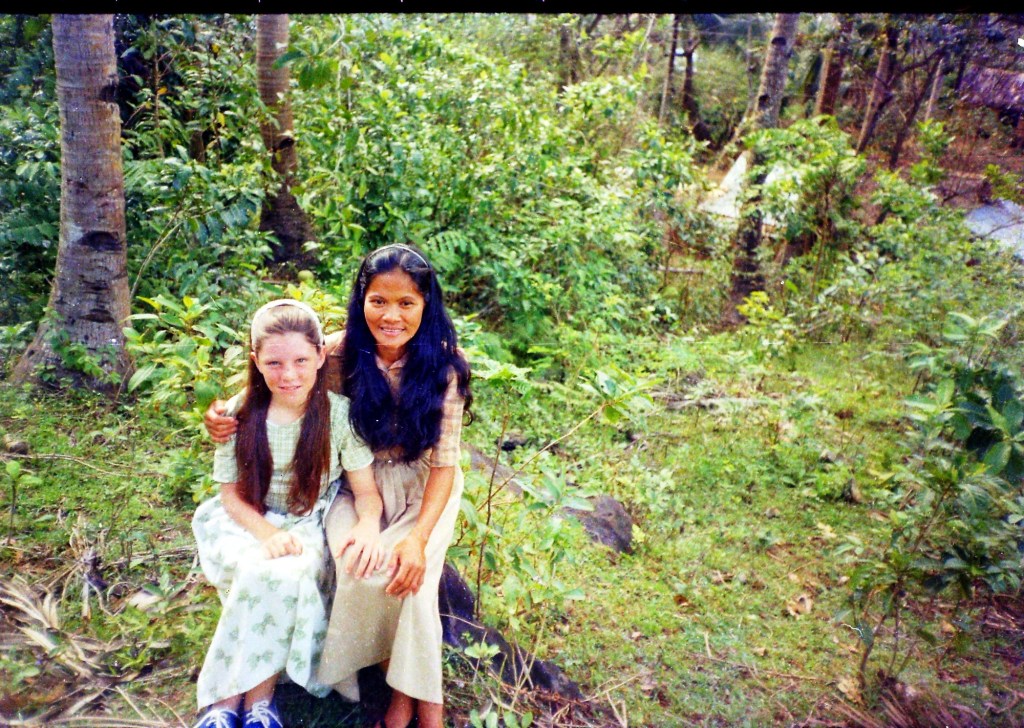

We had no money for luxuries. I owned one pair of sandals, worn until holes cut through the soles. Birthdays were not something I looked forward to and holidays went uncelebrated— except for the small mercy of my grandfather, who sent $10 for birthdays and $25 for Christmas a few years into our stay in the Philippines. For a few weeks, at least, I felt like I had enough.

Other injustices cut deeper. I remember being accused of eating banana-nut bread my mother had bought to share. Josh insisted I was guilty, and my mother spanked me twenty times, demanding I “tell the truth.” I continued denying it until finally, exhausted and broken, I admitted to something I hadn’t done. The truth came later: neighbor children had stolen food from the house. By then, the damage was done. I learned that my voice didn’t matter; others’ lies could define my reality.

The most humiliating memory came when I was ten. We were staying overnight at someone’s home when their kingfisher bird was found injured, a nail-spiked board lodged in its beak. Surrounded by nearly twenty children, Josh seized the opportunity to accuse me. In truth, I had been with a friend and never even saw the bird until the next morning. My mother dragged me into another room and spanked me again and again until I confessed. Then Josh forced me to speak into a microphone, apologizing to the crowd for breaking the bird’s beak and for “lying.” I was mortified, especially in front of the boy I had a crush on. Even when the truth surfaced later — that another child had been responsible — the sting of that public humiliation never left me. It scarred me so deeply that for over twenty years I continued to remind my mother of how she had wronged me. It was only then that she finally admitted I had been falsely accused.

Through all of it, I clung to my father more than my mother, because at least he wasn’t the one delivering the spankings. But looking back, neither protected me. My father spent most of his time asleep or locked away listening to faith-healer tapes, only surfacing to attend church services or exercise his authority. My mother worked constantly, her energy drained by survival. And I — like all children in that world — had no choice but to endure.

Leave a comment