Chapter Three: Puro Beach

They say childhood is the soil where the seeds of our identity take root. Some are planted in love, others in chaos—but all of them shape the way we bloom. My early soil was unpredictable. A mix of sacred beauty and emotional erosion. It was at Puro Beach, our second home in the Philippines, that I began to understand how environment, neglect, and gendered expectation could quietly carve away at a child’s self-worth—and how the body, even then, would absorb it all and hold it until the day I was strong enough to let it go.

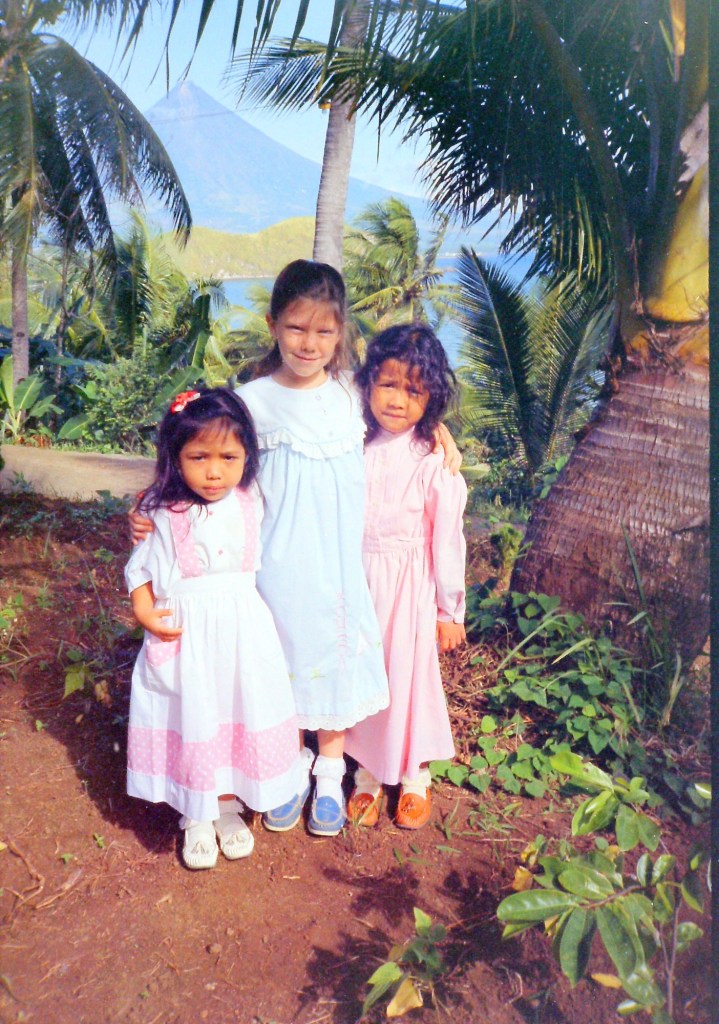

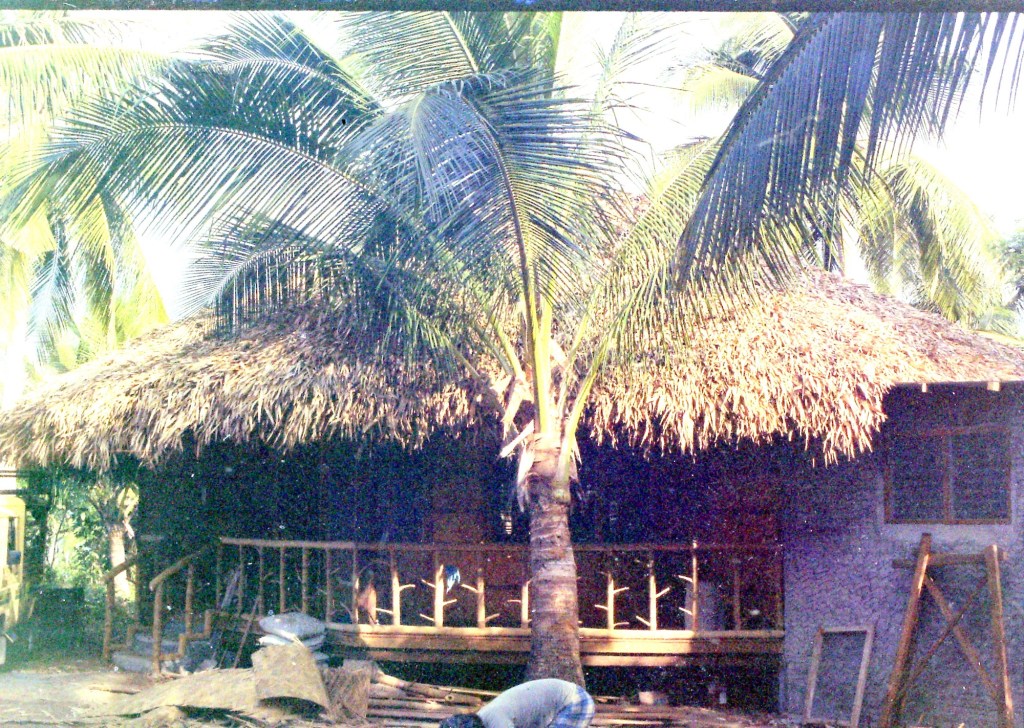

Puro Beach was breathtaking—on the outside. Our hut sat perched above the sea, with a view of Mayon Volcano in the distance. Palm-frond rooftops, bamboo floors, woven rattan furniture… it felt like something out of a travel magazine. Until the storms came. Until the rats returned. Until the roof leaked. Until the weight of survival eclipsed the wonder of it all.

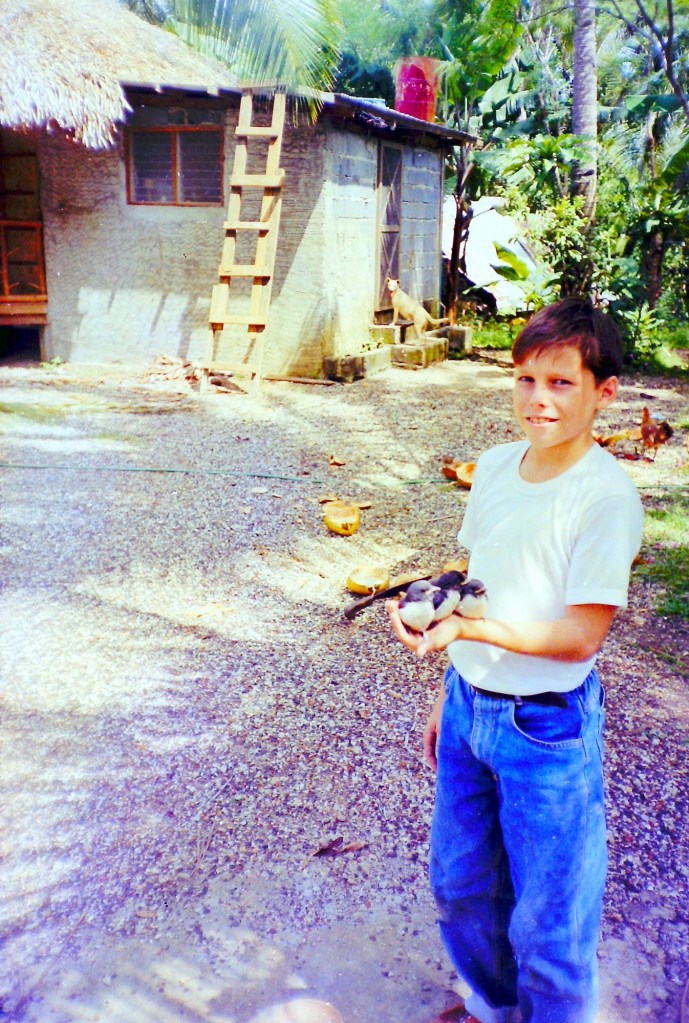

We lived off-grid, long before that was a trend. Our showers were cold. Our roof leaked during every typhoon. Geckos would crawl our walls and honeybees nested inside them. We used pans to catch the rain that dripped through the roof, and I learned to patch leaks with whatever we had. It wasn’t just resourcefulness—it was adaptation, born of necessity.

I had no mattress. I slept on a plastic mat on a slat bed. My brothers shared a room. My father built a church next to the hut where services lasted hours, and the benches left your bones aching. I’d sneak away to nap on the floor in our living room and return before the sermon ended, pretending I was still present. That became a pattern in my life—disappearing internally while keeping up the appearance of devotion.

But the most profound element of my time at Puro wasn’t the hut or the heat. It was the growing ache of loneliness.

My brothers were allowed to play, roam, and explore. I was told to clean. To serve. To polish floors. To hand-wash clothes. To cook. At four years old, I was already initiated into womanhood through chores, restriction, and exclusion. The message was loud and clear: boys get freedom, girls get responsibility. Boys are fun, girls are burdens. It made me wish I had been born a boy. Anything to escape the cage of expectation I was in.

My childhood was not shaped by connection—it was shaped by detachment. We moved so often that I learned to let go before ever letting in. I stopped forming bonds because I knew they wouldn’t last. Even with my brothers, I was an outsider. I wasn’t just the youngest—I was the unnecessary one. My presence was tolerated, not welcomed. I learned to silence my voice. To not ask. To not need. To not feel.

But one moment would forever fracture my sense of safety.

I was four years old. My mother was overwhelmed—my father offering no support, as usual. She called me into her room, crying. Her voice shaking. And then she said the words no child should ever hear: “I can’t handle the kids anymore. You guys have to move out.”

She meant it. She told me to pack my things in the middle of the night. I had nowhere to go. I sobbed, asking to stay until morning because I was scared of the dark. I remember looking at the door and wondering how I’d find a bus to Edna’s house—the only woman I thought might take me in. That night, a part of my innocence shattered. It wasn’t just abandonment—it was betrayal. I was not just unwanted. I was unsafe in the one place where I should have been held.

That experience taught me not to trust. Not to rely. Not to need. It made me harden. It made me decide: I will take care of myself. No one else will. And that belief stayed buried in my nervous system for decades.

When I started school at age five, I passed a placement test and skipped two grades. I walked to school alone, dodging stray dogs and men with knives. One man came out of his house waving a blade and pointing at me. I ran the rest of the way, terrified. I began carrying an umbrella just to defend myself from dogs that lunged at my legs. There was no protection. No escort. No check-ins. Just faith that I’d make it home alive.

The kids at school weren’t kind. I was the foreigner. The “American.” I was pinched, taunted, isolated, my hair was pulled or snipped with scissors. My food was stolen. My belongings taken. One teacher even humiliated me publicly after I took a sip of a soda she sent me to buy for her—because I was hungry. She looked at me and said, “I thought Americans had money.” Shame burned through me. I wasn’t just hungry—I was invisible.

We had no money. My father had spent our savings building churches, traveling to preach, giving everything we had to others—while we had nothing to eat. My mother had to get a job in town. I started stealing money out of my mothers purse for lunch. I took five pesos once and bought fish and rice, eating it like I hadn’t had a full meal in years. I remember that day clearly. Not because I stole. But because it was the first time I fed myself without guilt.

Most days I ate powdered milk mixed with rice for breakfast and a santol fruit for lunch, because it cost only one peso. I ran tabs with the lunch lady. I begged classmates to share. My brothers, meanwhile, used their money on video games. My parents were so neglectful that they only discovered Ben was skipping school to play video games every day after being told he had to be held back a year. I learned early that I would need to fight for my own survival. That food—love—attention—were things I had to negotiate for.

And yet, even in that poverty, my father still found a way to withhold. He had his own stash of butter and made us use margarine. He’d cook spicy meals I couldn’t eat, tell my brothers that if they didn’t eat spicy food they weren’t men, then forget to make a separate batch for me. Spaghetti, mung bean soup, chili-pepper-covered everything. I went to bed hungry more nights than I can count. I can remember sitting on his lap only once in my life. Affection was rare. Affirmation even rarer.

But the cruelty didn’t always come from neglect. Sometimes, it was deliberate.

Joshua—the brother who blamed me for everything—was always believed. If he broke something, I was punished. If he lied, I took the fall. I was spanked until I confessed to things I hadn’t done. I learned that my truth didn’t matter. That being innocent didn’t mean being safe. That crying didn’t get you comfort—it got you more pain.

There were countless incidents where Joshua blamed me in front of a crowd of dozens of children for things I did not do. I was forced one time to apologize over a microphone, crying, while he stood smug. My mother gripped my wrist so hard on the walk home it left a mark.

These moments taught me that my voice was not welcome. That my pain was not believable. That love was conditional and could vanish at any time.

I stopped defending myself. I started lying to avoid pain-after the 20th spanking. Not because I wanted to lie. But because it was the only tool I had to survive.

And yet, somehow, within all this—there were moments of beauty. Of ocean swims and guava trees. Of warm sun on my back and skateboards down steep hills. I remember climbing trees, laughing, escaping—if only for an afternoon.

I also remember sleeping on dirt floors while visiting churches on other islands. Eating with my hands beside families who had little but gave us everything. The Filipino people taught me generosity. My family taught me how to endure.

My father idolized faith healers. He believed he had their “anointing.” He’d listen to tapes of William Branham or Freddy Clark for hours. We, the children, were background noise in his pursuit of spiritual status.

He slept most of the day. My mother did everything. I watched. I cataloged. And I made a silent vow:

I will never be like them.

I will never be a doormat like my mother.

I will never marry a man like my father.

I will never trade my truth for acceptance.

And I will never raise a child the way I was raised.

This chapter of my life was not just the continuation of my story—it was the crystallization of my identity. The pain became the map. The silence became the teacher. And the girl who once thought being born a girl was a curse is now the woman who sees her feminine as her greatest strength.

Because now I know: being born into dysfunction does not mean you are destined to stay there.

And I didn’t.

Leave a comment