Chapter Two: Culture Shock

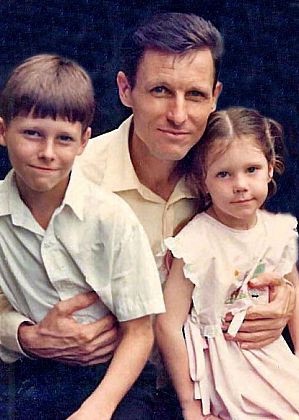

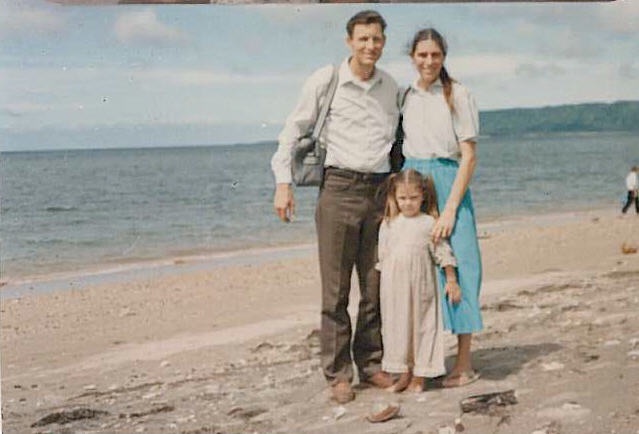

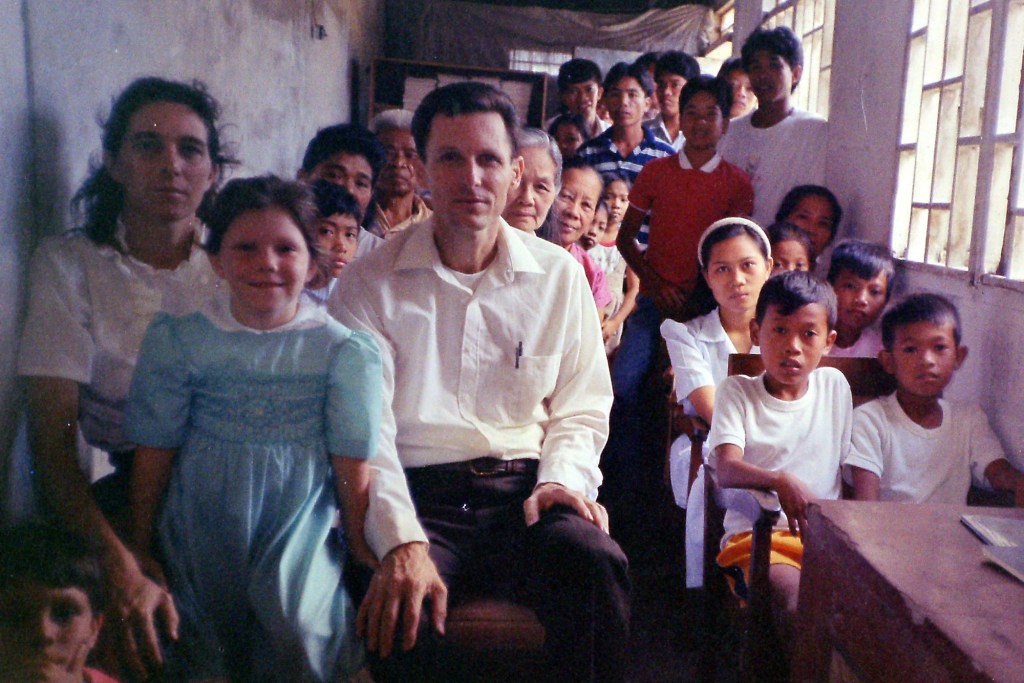

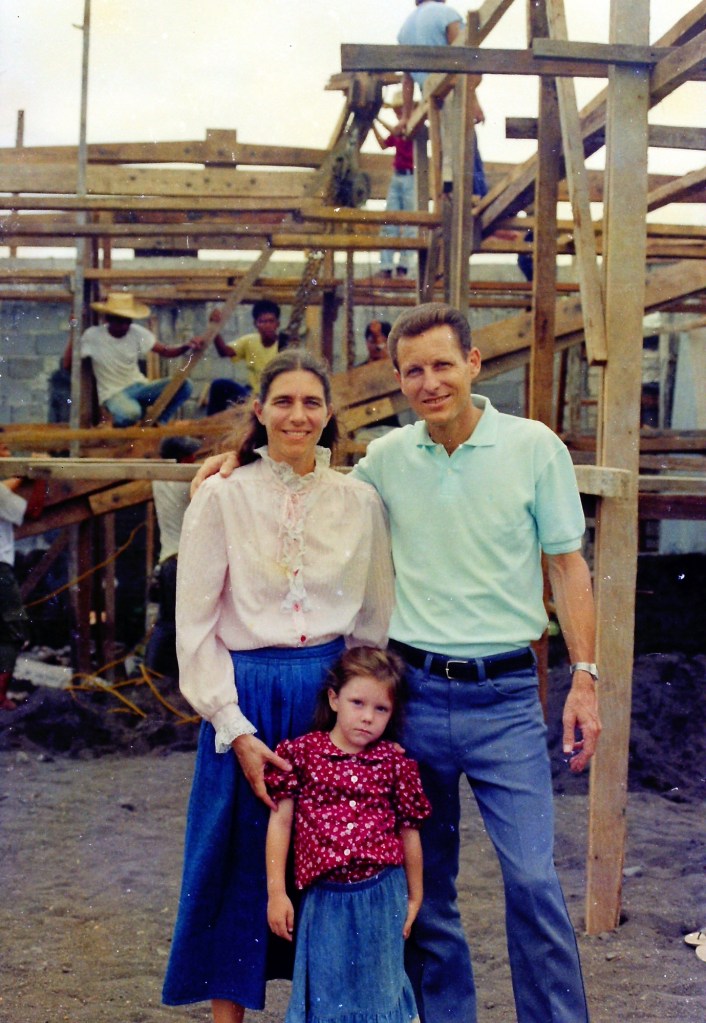

In 1989, my life shifted from the familiar to the foreign. Our family relocated from California to Manila, the chaotic capital of the Philippines—a move my father claimed was divinely inspired. It wasn’t a relocation; it was an upheaval. We were not tourists. We were missionaries, stripped down to the bare essentials, living in borrowed spaces, carrying the burden of a belief system that demanded obedience in the name of salvation.

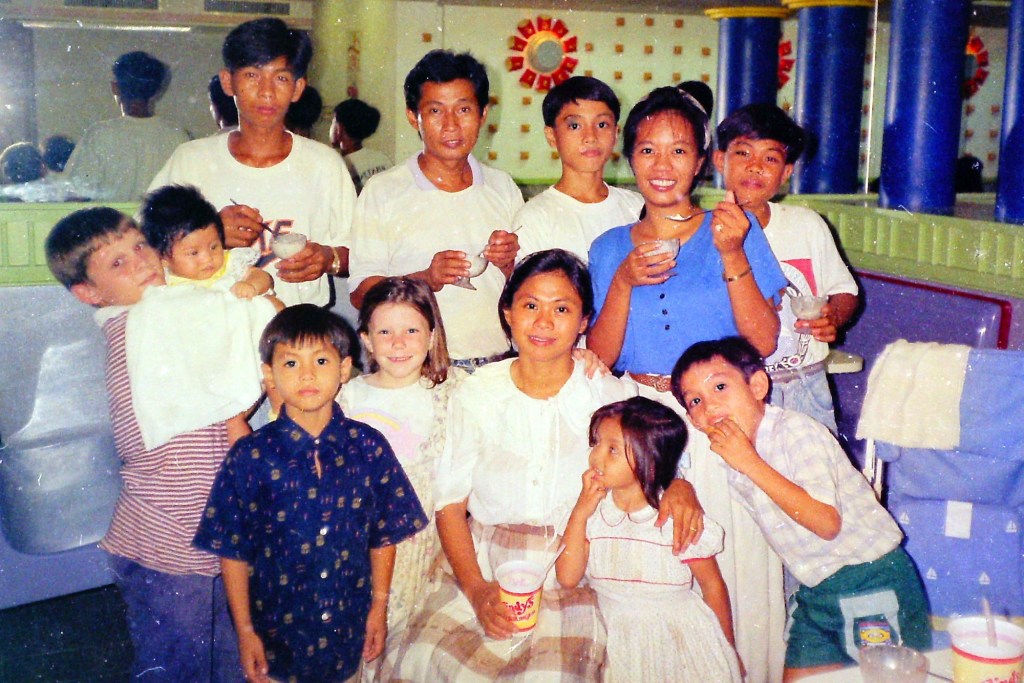

We first lived with a local church family before eventually moving to Ligao, a rural town that would become the backdrop of some of my earliest memories of resilience. There, we moved into a modest two-story apartment where my father began hosting church services. Eventually, he broke ground on a small church building nearby—his version of planting seeds for the kingdom. But what was claimed as sacrifice for the gospel often came at the expense of emotional safety, consistency, and basic protection.

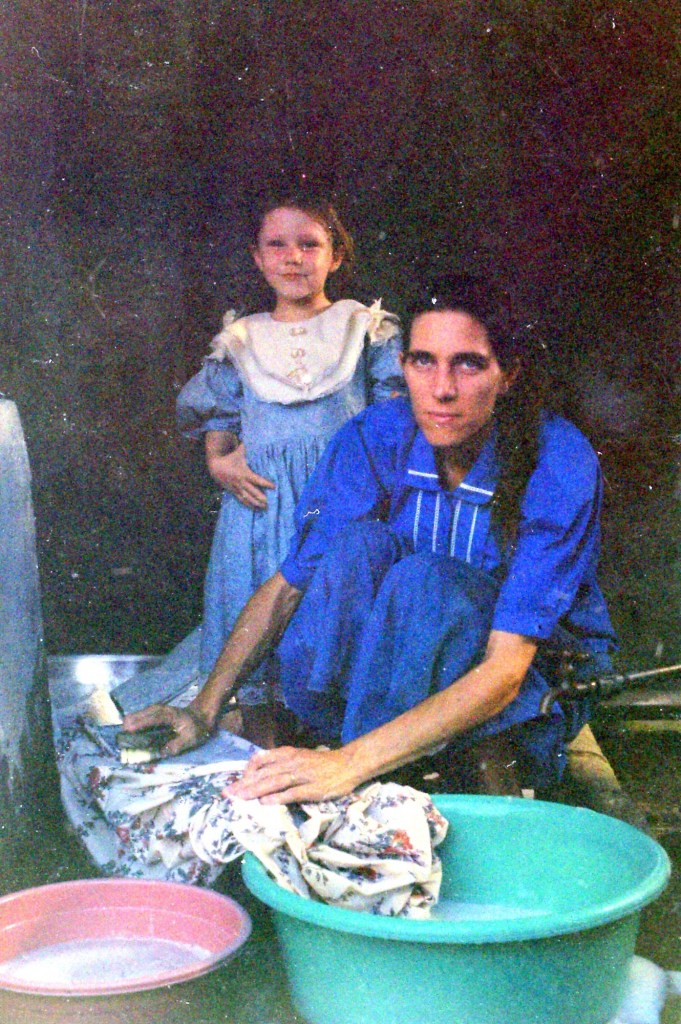

Shortly after we arrived, my mother and I both fell seriously ill with typhoid fever. My mother’s condition became life-threatening. My brothers were distracted with their own social lives, and my father, absorbed in his mission, was emotionally unavailable. So, at just four years old, I became my mother’s caregiver. I sat with her, checked on her, stayed close while she writhed in pain. This wasn’t an isolated moment—it was the beginning of a pattern where I was expected to take on emotional responsibility far beyond my years. What most children are protected from, I was immersed in.

That same year, my father decided I was capable of walking myself to school. Alone. In a third-world country. My mother tried to intervene, but he refused to be challenged. So I walked the cracked, crowded roads each morning across a traffic-filled road to the school—my small feet navigating unfamiliar terrain, my nervous system absorbing the unspoken rule: No one’s coming to save you. You’ll have to save yourself.

I developed a hyper-awareness that most adults don’t even possess. I learned to scan my surroundings. I paid attention to the faces that lingered too long. I memorized escape routes, even though I had no words for what I was doing. Survival became second nature.

I still remember the day I stood at a crowded intersection beside a tall woman. I looked up at her and thought, I hope I grow up tall like her. I was four.

When I graduated kindergarten with honors, my medals were withheld. The teacher informed us that American children didn’t deserve Filipino recognition. We later learned she was grieving the death of her husband—a man who had lived a double life with another family. I had unknowingly become the target of displaced rage and heartbreak. Once again, I became the landing place for someone else’s unprocessed pain.

Danger wasn’t abstract. It was visceral.

One day, on the way to church in a tricycle taxi, a man jumped in front of our vehicle. The driver fled. My mother and I remained trapped. The man shoved his bleeding arm through the windshield, a dagger aimed just inches from my face. He tried to drag me out by my skirt. My mother froze. I screamed. A gunshot rang out—a police officer chasing the man had fired. He hit him in the leg. Another church member pulled me to safety. And still, weeks later, another man entered our home with a knife. This time, it was my nine-year-old brother who saved us. He kicked the man, who dropped the weapon and ran.

But we didn’t just experience danger. We were expected to normalize it.

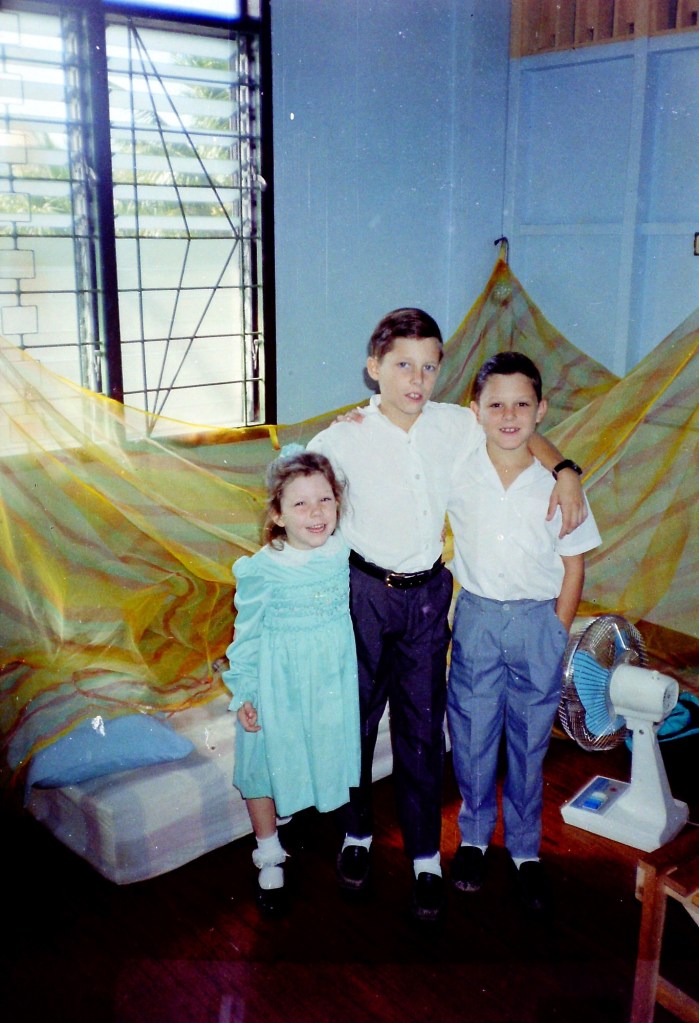

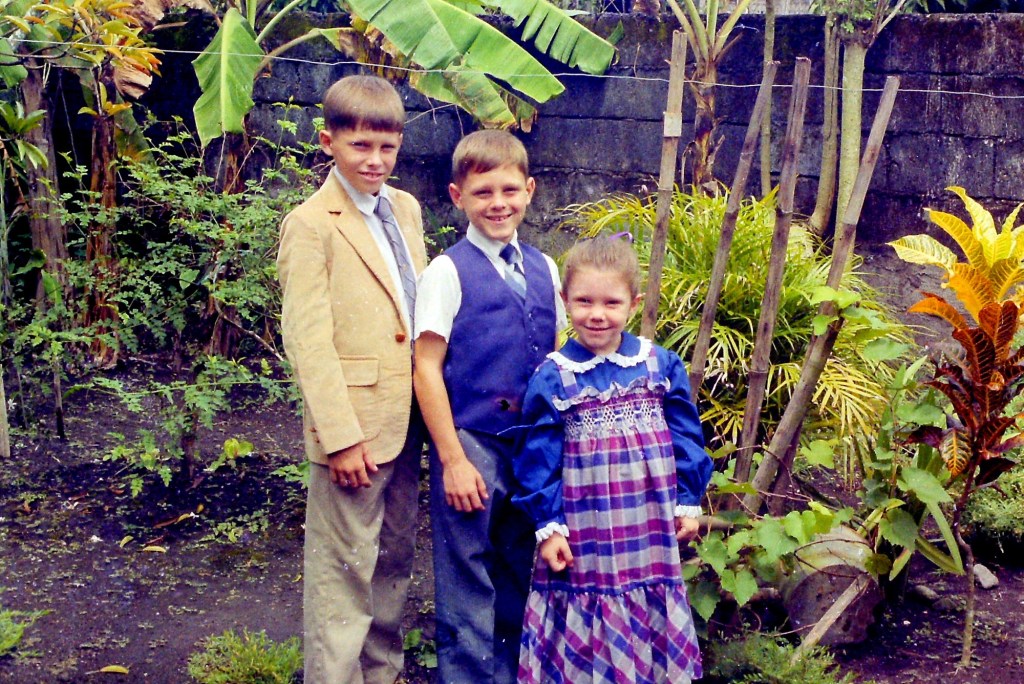

That same man’s wife showed up at our door weeks after the attack, asking for help. My father gave her husband a few pairs of pants. No police. No consequence. We moved shortly after, but the memory came with us.

The layers of trauma didn’t stop there. My brothers, at ages seven and nine, were circumcised—not as infants, but as children old enough to feel everything. My parents explained it as religious integration. In truth, it was to spare them from the mockery of local boys who somehow knew their bodies didn’t match. Who was looking at them? Why was that pressure considered more important than their emotional well-being? My brothers bore that pain publicly, in a culture that treated their suffering as a rite of passage. But I saw the quiet shame they carried.

And then there was the deeper programming—the conditioning.

My mother had been denied the wedding of her dreams. That loss became a wound she unknowingly passed to me. From a young age, I inherited the fantasy of the perfect marriage, the desire to be chosen, the belief that I would only be whole when completed by someone else. My earliest dream wasn’t to become a doctor or a leader. It was to be a devoted wife and mother. That was the path I was taught. Independence was not modeled. A career outside the home was never discussed and explicitly forbidden. I was groomed for a life of obedience, not sovereignty.

Church services became the rhythm of our existence—twice on Sundays, once mid-week. They weren’t nurturing. They were punishing marathons of fire-and-brimstone sermons. Children were expected to be perfectly still or face physical consequences. My brothers tracked the number of spankings they’d get just for shifting in their seats. Fear wasn’t a side effect—it was the method of control.

Still, amidst the pain, there was magic. There was childhood.

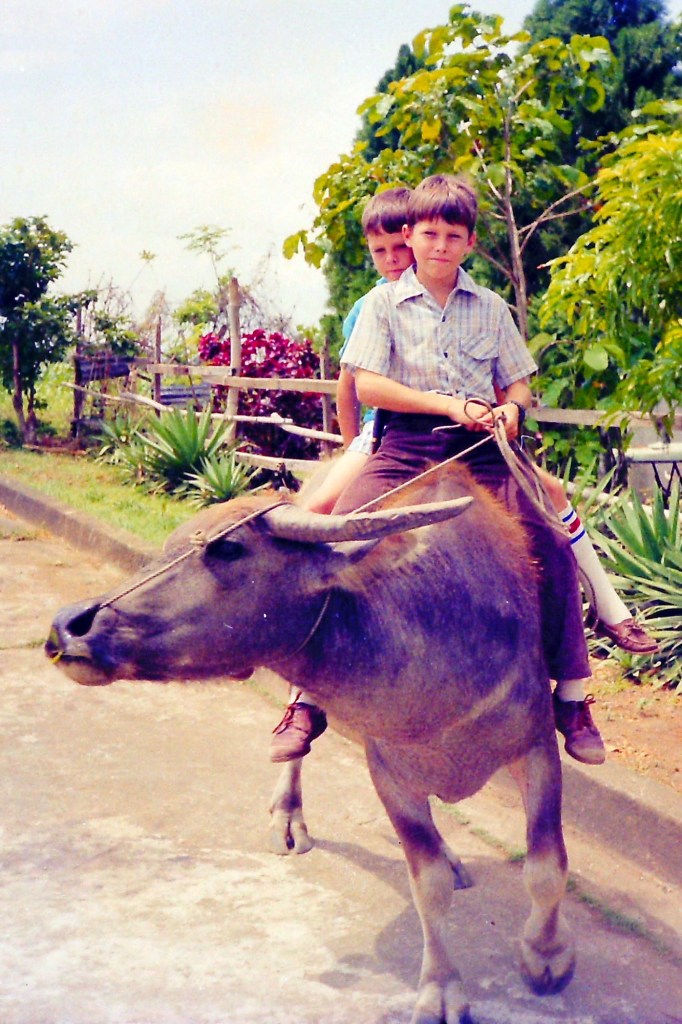

I remember skateboarding down the steep hill near our friend’s house, wind tearing through my hair, laughter echoing against the coconut trees. We climbed, we ran, we explored bat-filled caves. We played with local children who didn’t speak our language but spoke the same one where it mattered—curiosity, joy, mischief. The Philippines gave me moments of beauty. Simple pleasures. Wonder. Freedom. But always with an undertone of danger, always laced with the need to stay on alert.

We lived through typhoons and power outages. We made do with little. And yet, some of my fondest memories were formed there. The land, the people, the contrast—it all shaped me.

But the most profound shaping didn’t come from the culture. It came from what I wasn’t given.

No one ever asked me how I felt.

No one ever asked if I was scared.

No one ever asked what I needed.

No one explained why grown men with knives kept trying to hurt me. Or why children my age in the hills were being trafficked. Or why I was left alone to navigate it all with a smile and a song.

So I became two people: the obedient girl on the outside, and the ancient soul awakening within.

The child in me survived what should have broken her. But the woman I’ve become is the one who returned, gathered those fragmented pieces, and wove them into power.

I no longer believe resilience is a badge of honor for what we should have been protected from. But I do believe that the ones who survive can transmute pain into purpose. I am one of them.

This period wasn’t just about culture shock—it was about seeing through the illusion. It was about waking up to the dissonance between what was said to be “God’s will” and what felt innately wrong in my body. It was about learning how to listen to my instincts, even when no one else did.

I now walk with the part of me that once walked alone.

And I listen deeply to the little girl who learned, far too early, that sometimes the only one who can keep you safe is you.

Leave a comment