Chapter One: Born Into Belief, Reborn Into Knowing

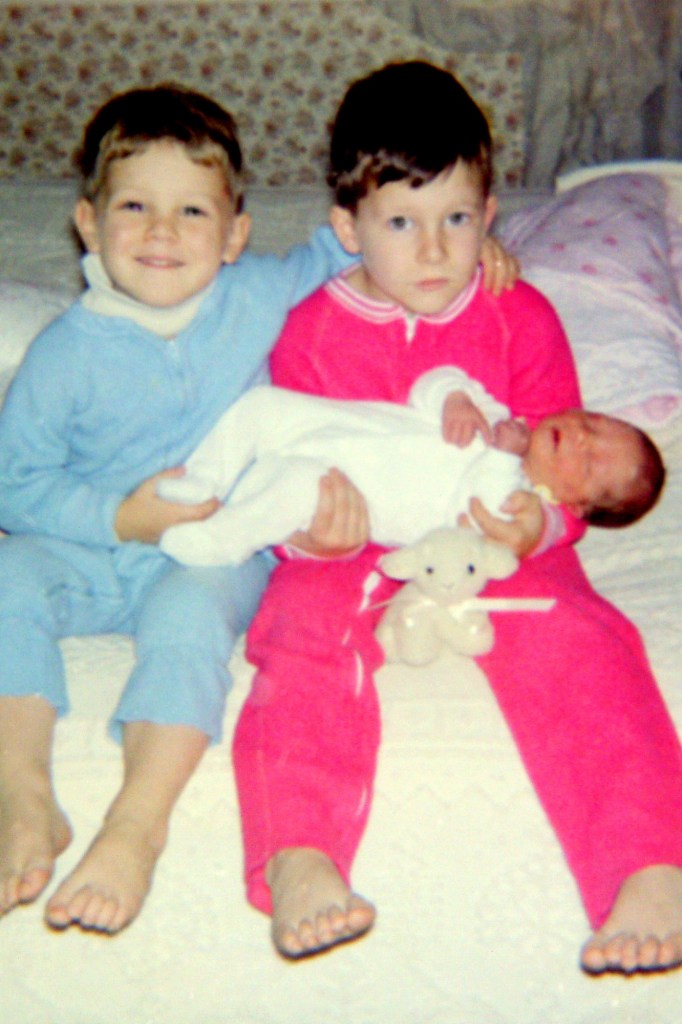

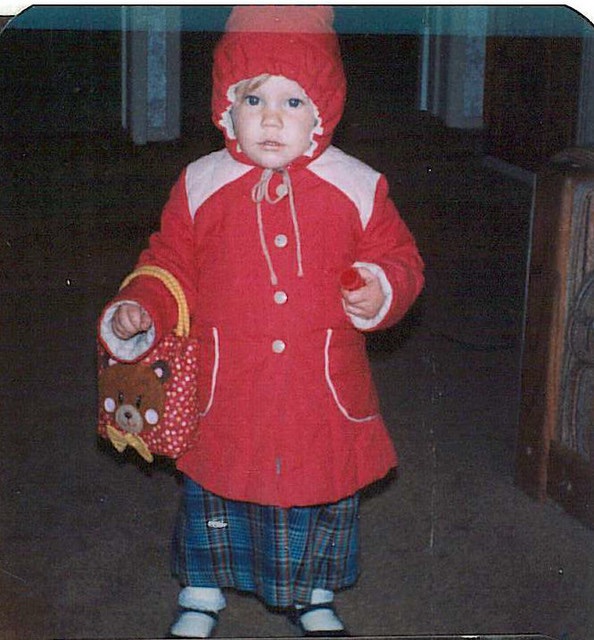

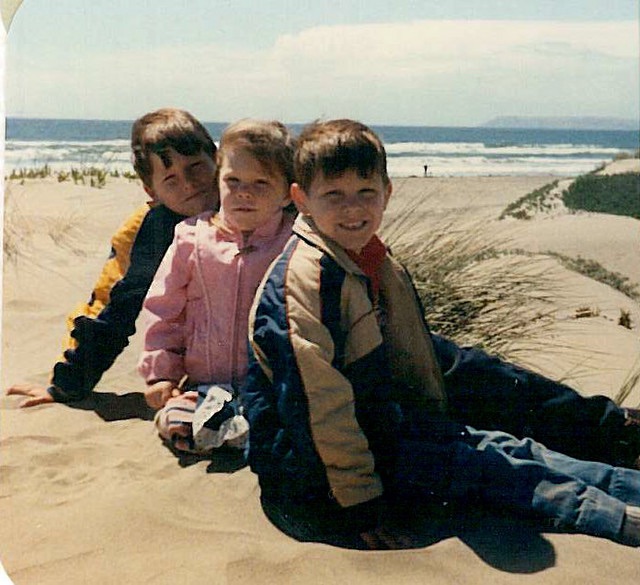

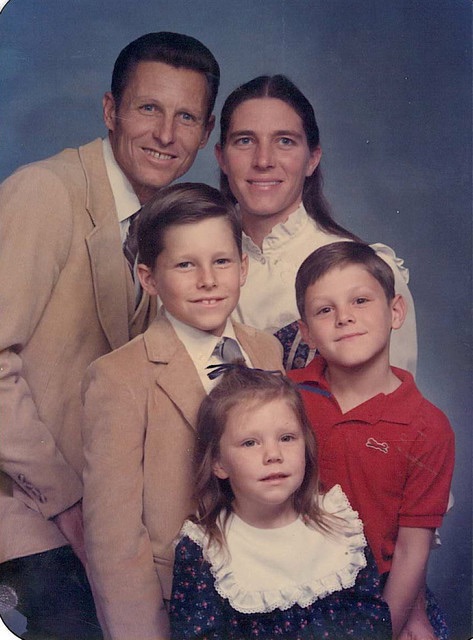

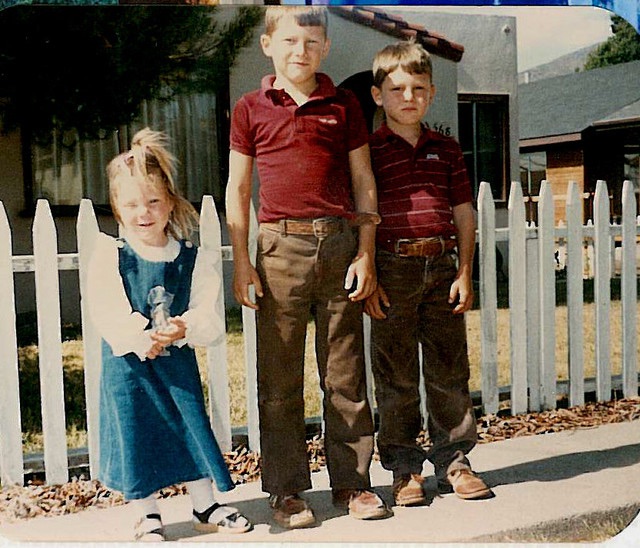

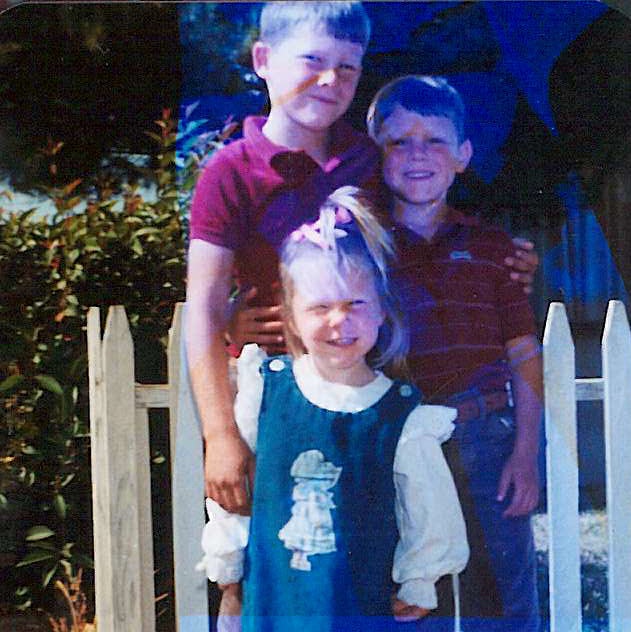

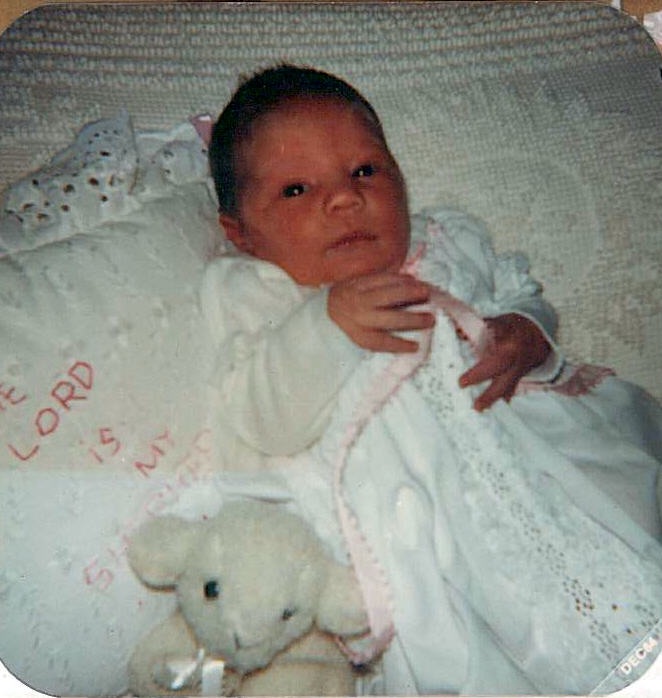

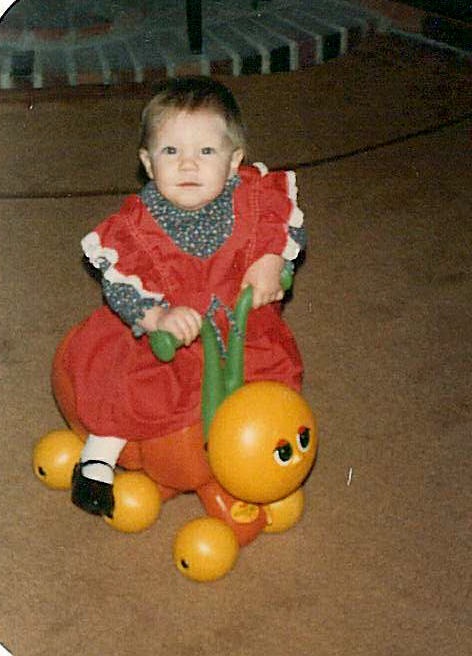

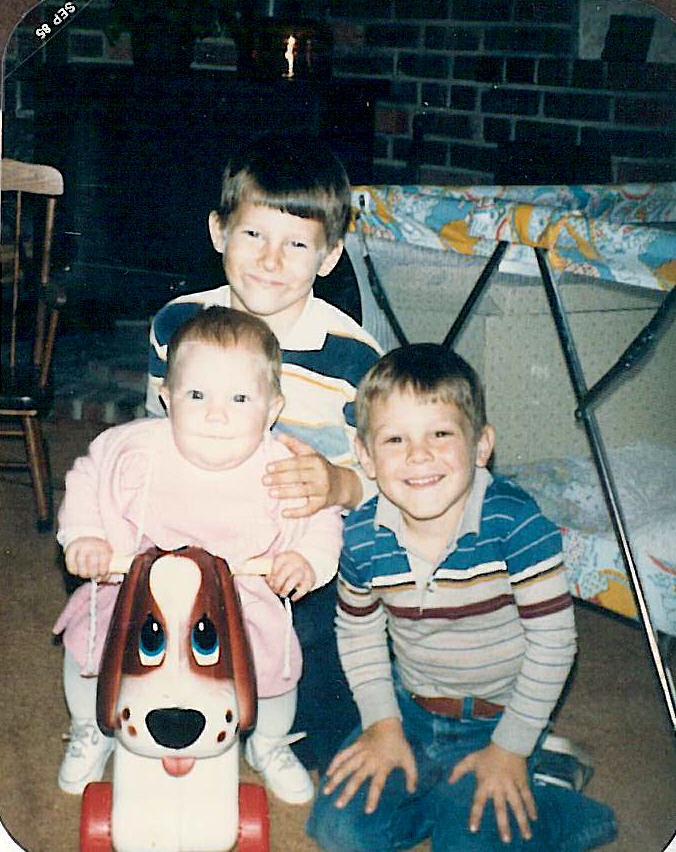

I entered this world under the soft skies of Atascadero, California—an unsuspecting infant soul dropped into the midst of a deeply religious and toxic household. I was the youngest of three, born into a home where conviction came before curiosity, and unquestioned obedience was considered the highest virtue. My arrival completed the trinity of children in a family governed by spiritual fundamentalism cloaked as faith, yet rooted in trauma, fear, and control.

I grew up surrounded by devotion that masqueraded as divine order. But beneath that devotion was a complex weaving of unresolved lineage pain, inherited trauma, and spiritual bypassing disguised as righteousness. From the outside, we were a family of faith. But the foundation upon which that faith rested was unstable—formed not by love, but by the unhealed wounds of generations past.

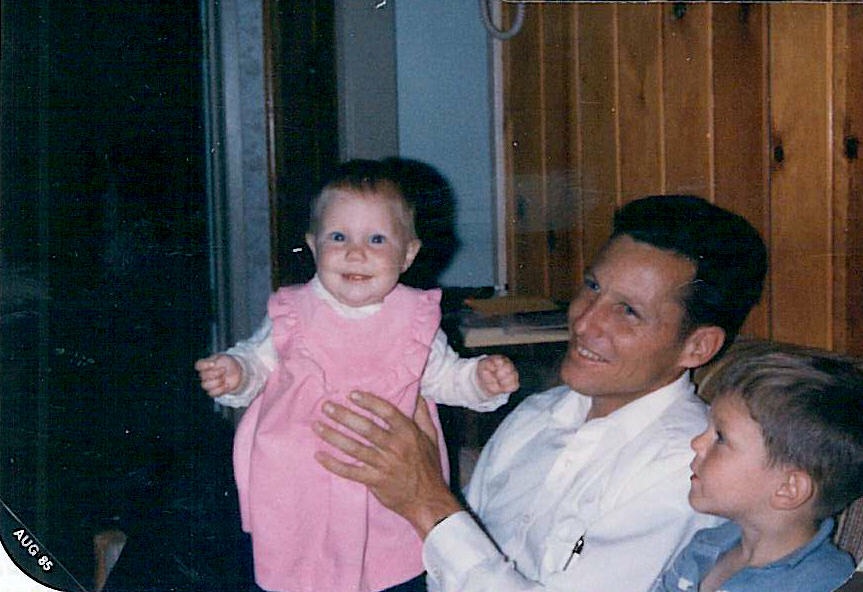

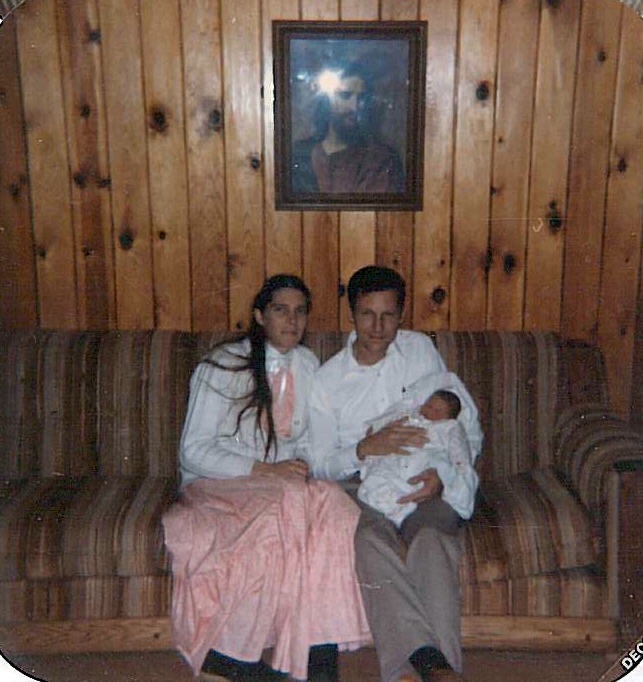

My parents met in a space of brokenness—Alcoholics Anonymous—a place of healing that became the ignition point for a codependent entanglement sealed by desperation and divine delusion. My father, recently released from prison for drug peddling, had found a new identity in religion while behind bars. My mother, a woman once filled with promise and privilege, had just tried to end her life in the ocean. She told the story of being pulled from the undertow by the voice of God, urging her to gather her things and move west. It was in California she met my father. He held a Bible under his arm. She mistook certainty for salvation. They married after knowing each other for a week and a half.

This was the foundation of my family: trauma bonded by theology. And I was born into their story as both witness and unwitting participant.

My mother, once a tennis champion from an affluent East Coast family, was slowly hollowed out. She went from sailing yachts and skiing mountains to surrendering every ounce of her autonomy. Under the guise of submission and “God’s will,” my father demanded she discard all clothing that resembled masculinity. Her short hair, her independence, her past—each became a sin to be purged. By the time I was old enough to observe, her spirit had already dimmed. She was afraid of her own voice. And I watched her, silently absorbing the message that a woman’s safety lies in compliance.

My father was not born cruel—he was forged in suffering. Disowned by his biological father and beaten by his stepfather, he survived by adapting to dysfunction. As a young boy, he reported his mother’s affairs to avoid punishment, only to witness her being beaten unconscious. He joined the Marines seeking structure, but loss followed him there too—his mother took her own life, and her funeral spared him from dying with his battalion in Vietnam. That paradox—life spared by death—became a crucible that formed his devotion to faith. But it wasn’t surrender—it was a survival mechanism. Religion became his control rod for the chaos he couldn’t reconcile.

And then came William Branham—the so-called prophet who shaped our world. My father discovered him while incarcerated, and from that moment, the trajectory of our lives was cemented.

Branham’s teachings weren’t simply sermons—they were psychological programming. He taught holiness, but it came with fear. He spoke of miracles, but demanded obedience. He heralded the apocalypse, instilling in us a sense that death could come any moment—and if we weren’t pure enough, we’d be left behind.

I internalized that terror.

As a child, I was haunted by the rapture. Night after night, I dreamed of my family ascending into the sky while I remained, condemned and alone. I’d wake up gasping, drenched in sweat, running down the hall to check if my parents were still there—terrified I had been abandoned by both them and God. I didn’t know it then, but this was my first introduction to spiritual trauma—the kind that roots itself so deeply into your nervous system, it becomes the rhythm of your breath and the tightness in your chest.

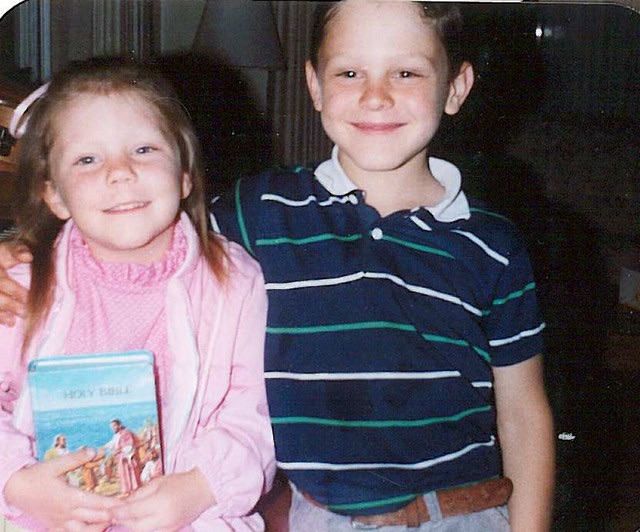

Questioning Branham’s teachings was unthinkable. To doubt was to endanger your soul. To think critically was to risk eternal damnation. So I became the perfect believer. I read the Bible from cover to cover before the age of ten. I fell asleep to Branham’s voice on cassette, hoping that by osmosis, I could absorb enough righteousness to survive the second coming.

But it wasn’t just about survival. It was about belonging. You were either chosen—or forsaken. And I needed to belong.

Branham’s worldview, especially about women, shaped the way I saw myself. My body, my voice, even my thoughts were filtered through the lens of submission and shame. Women were not to lead, not to teach, not to desire power. My role was to be modest, silent, and devoted. My goal in life? To be a perfect wife and mother, invisible in my own divinity.

Yet, even in the depths of this indoctrination, my spirit whispered that something was off. I couldn’t name it then, but I felt it—a quiet inner knowing that the God I loved was not the God being preached to me.

I grew up in a house that welcomed strangers—homeless men, addicts, drifters—all brought in by my father under the guise of ministry. He’d rescue them, pray over them, give them shelter. But the burden fell on my mother, already drowning in her own fears. When she voiced her resistance, she was reminded that her husband spoke for God, and to oppose him was to oppose divine will.

That’s the power of religious manipulation—it hijacks your sovereignty and calls it salvation.

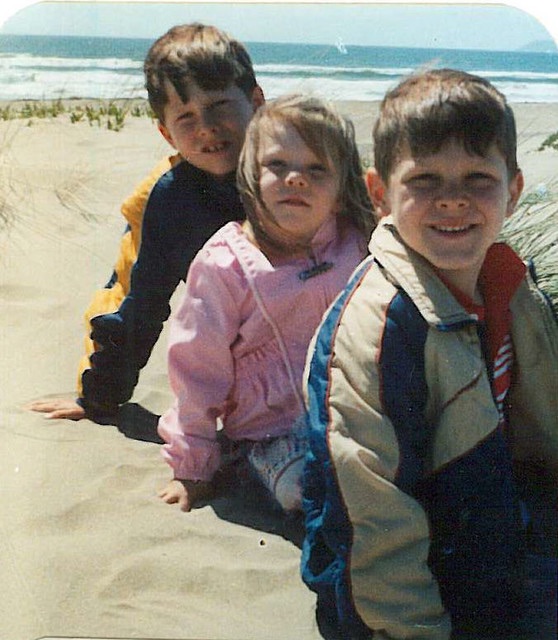

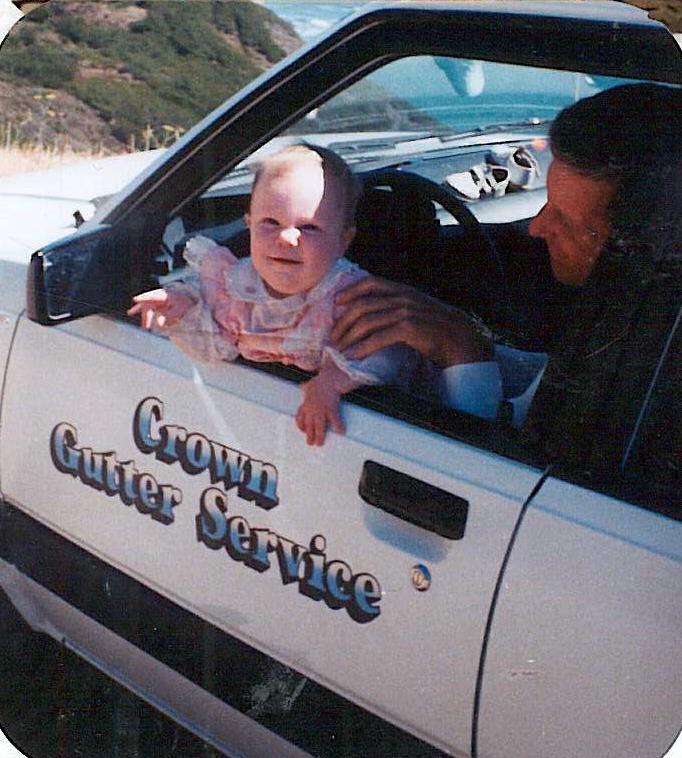

At age four, we gave everything away. My father believed God had called us to be missionaries in the Philippines. He sold his business, gave away our belongings, and uprooted us to a third-world country based on a vision. I didn’t have the language for it then, but I now understand that I was being trained for something far greater than I could comprehend. I was being forged in the fire of self-sacrifice. Of seeing others’ pain. Of being immersed in service. Of surviving chaos by becoming the healer.

What some might call a traumatic disruption of childhood, I now understand as the very foundation of my calling.

Because beneath it all—beneath the fear, the dogma, the indoctrination—there was love. Not the love that was taught to me through punishment and piety, but the love I felt when I looked into the eyes of the broken, when I offered presence to those society discarded, when I prayed not out of fear, but from the aching center of my heart. That was the God I knew. That was the part of me that would one day rise from the ashes of my upbringing and become the woman writing these words.

I now see clearly that I was born into a system built on fear so I could become a woman rooted in truth. I was raised in a house of illusion so I could break the generational trance. I lived under the rule of false prophets so I could awaken the real voice within me.

This chapter of my life wasn’t just the beginning of my story—it was the beginning of my unraveling. And it’s in the unraveling that I found who I truly am: not a woman molded by religion, but a sovereign soul reclaiming her divine design.

Leave a comment